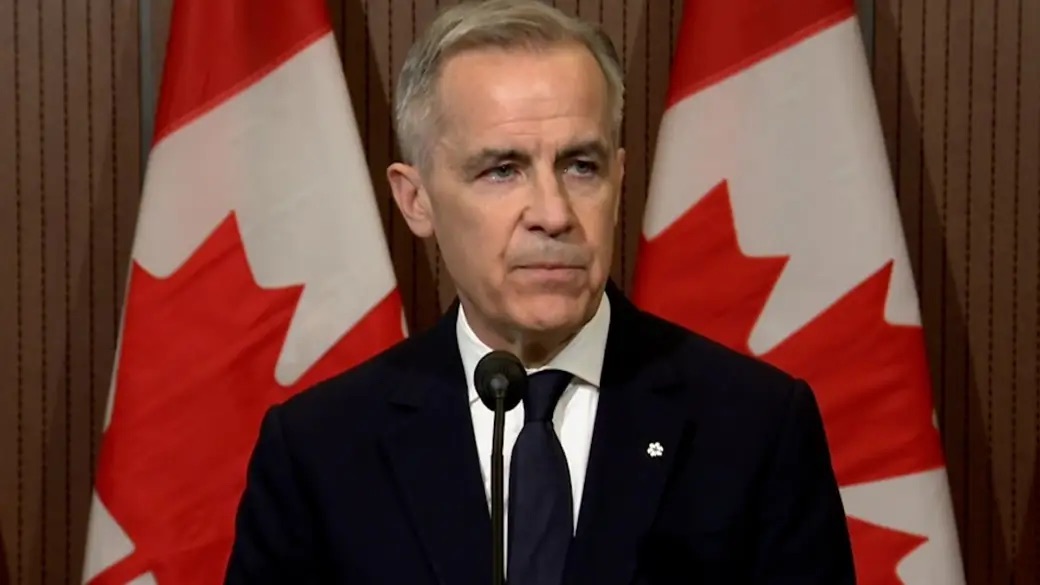

It was a spring morning in Ottawa when the news broke like a thunderclap across the nation—Canada would strike back. The airwaves buzzed with urgency as Prime Minister Mark Carney, flanked by a cluster of advisors and premiers, stepped up to the podium. His voice was steady, but the message was unmistakably bold: Canada would match the United States’ 25% tariff on imported vehicles. The move, a direct response to former U.S. President Donald Trump’s sweeping “Liberation Day” trade measures, signaled a new chapter in North American economic relations—one where Canada would no longer play defense.

The tariffs, effective April 3, 2025, target U.S.-made vehicles that do not comply with the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), but notably exclude auto parts. This strategic carve-out was designed to protect the deeply integrated supply chains that keep factories humming on both sides of the border. But even with that safeguard, the ripples were immediate.

In Windsor, Ontario, the heartbeat of Canada’s auto industry, the impact was felt within days. Stellantis, one of the region’s largest employers, announced a temporary production halt and laid off 900 American workers. The company cited “supply instability and cross-border uncertainty” as key reasons. Meanwhile, the Global Automakers of Canada warned that consumers should brace for higher prices and potential delays in vehicle availability. Unifor President Lana Payne didn’t mince words. “This could spiral into a continent-wide recession if cooler heads don’t prevail,” she warned.

Back in the political arena, the tariff saga became a rallying cry. Carney, who had paused his campaign trail to address the crisis, portrayed the move as a defense of Canadian sovereignty. “This is not just about cars,” he said. “It’s about standing up for Canadian workers and industries in the face of unjust aggression.”

Opposition leaders were quick to weigh in. Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre proposed eliminating the GST on Canadian-made vehicles, a move he argued would stimulate domestic demand and cushion the blow to consumers. “Let’s make it cheaper to buy Canadian,” he declared at a rally in Calgary. Meanwhile, NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh took a page from history, unveiling a “victory bond” program to fund new infrastructure and manufacturing investments. “Just like we did in World War II,” he said, “we’ll invest in ourselves to build a stronger, fairer Canada.”

The broader context painted a picture of escalating tensions. Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs were part of a sweeping doctrine of reciprocal trade, targeting global partners who, in his view, had taken advantage of American generosity. While Canada was initially excluded from the first wave of these tariffs, the auto levy was a clear message: no one was off-limits.

Carney, a former central banker with a reputation for calm under pressure, made it clear that Canada would not be cowed. In a televised interview, he said, “If the United States chooses to retreat from global trade leadership, Canada will step up. We’re already in talks with Germany and other allies to form a new coalition for fair and open commerce.”

As the dust settles and negotiations quietly begin behind closed doors, one thing is clear: this isn’t just a policy shift. It’s a defining moment in Canada’s economic story. And whether it’s remembered as a bold stand or a risky gamble will depend on what comes next.